Features

CAN WE PLEASE STOP CALLING ALL DANCE MUSIC GENRES ‘EDM’?

DJ Mag Digital Editor Charlotte Lucy Cijffers explores the rise of EDM, attempting to once and for all settle one of the most divisive arguments in dance music…

It first happened at a media dinner about five years ago. I was sandwiched rather uncomfortably between two older international journalists — one from Amsterdam and one from New York. As we sat watching a slideshow about a dance-music-meets-yoga festival heading to Thailand that following summer, Mr NYC commented that he hoped Carl Cox was playing because he was his “favourite EDM DJ right now”. Heads swivelled and hands were raised to mouths as Mr Amsterdam and I let out a gasp of unadulterated horror. “Carl Cox and EDM? You must be confused,” Mr Amsterdam managed to stammer as a slideshow of smiling festival-goers blitzing smoothies flashed up on a giant LED screen. A heated argument was had across my lap for much of the remaining presentation, giving me time to ponder how on earth Coxy and EDM had ever ended up in the same sentence — let alone one being uttered by a music journalist.

Seven elderflower cocktails later and Mr NYC was still insisting that EDM stands for Electronic Dance Music, and therefore includes all genres of music made with machines, from techno to breakbeat, Chicago house to jungle. Mr Amsterdam, on the other hand, was insisting that the term EDM was a product of American ignorance. “DJ Mag is British,” he said, gesturing towards me as I pretended to be fascinated by a plate of mini quiches. “In Europe, we class EDM as a sub-genre of dance music. EDM is that big room Martin Garrix crap that’s suitable only for the Disney Channel!”

The next thing I knew, someone had received a fast-flying mini quiche to the face.

It wasn’t the first time I’d seen tempers flare over this issue, and it certainly wouldn’t be the last. Over the last few years I’ve moderated countless comments about the meaning of EDM on DJ Mag’s social channels — very few topics spew up as much toxic bile from trolls as the great EDM debate. So perhaps it’s time to finally unpack what the term EDM really means and settle the score once and for all. Is it a genre-spanning term or a label for a specific sound — for “Disney Channel” dance music.

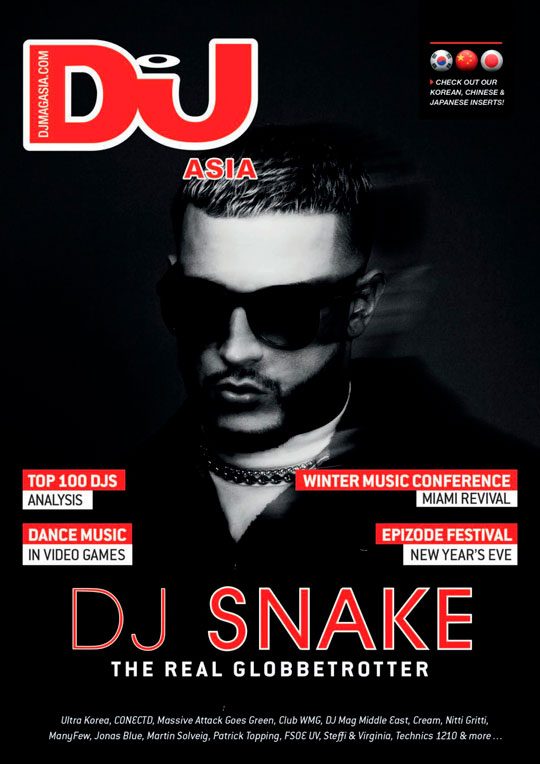

Screenshot from DJ Mag’s public Facebook page / 11th March 2018

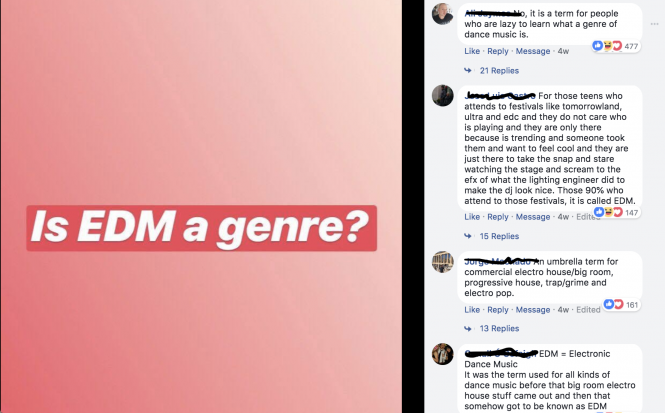

To understand the root of this community-dividing confusion, we need to go back. Way, way back, in fact, to early 2002. At the time, most kids Stateside were busy playing beer pong, drinking out of red plastic cups and flocking to the cinema to see movies about frat houses (Van Wilder, anyone?). Musically, mass marketed hip-hop reigned supreme, as Eminem famously spat out the words “Nobody listens to techno” in his charting-topping single, ‘Without Me’. His album ‘The Eminem Show’ would go on to be the biggest selling LP of the year, while Nickelback’s ‘How You Remind Me’ was the top single (FFS). In the UK we weren’t doing much better. Ronan Keating was topping the charts with insipid ballads, and manufactured acts like Sugababes and Atomic Kitten were at their latex-wearing, auto-tuned peak.

But there was one key difference between America and the UK in 2002, and that was the physical truth of Eminem’s sentiment. Nobody was listening to techno — in the U.S. at least — and not in anywhere near the numbers it commands today. House and techno had been all but ousted by American audiences following trance’s rise (and fall) in the early noughties — ironic considering the origins of dance music in Chicago and Detroit respectively. Both scenes in those origin cities had been pushed even further underground by the early-2000s, as acts like Richie Hawtin, Kevin Sanderson and Stacey Pullen decamped to Europe in search of bigger bookings and wider-scale appreciation. 2001 had also seen introduction of the federal RAVE act — the law that officially put the kibosh on raves nationwide and famously saw legendary New Orleans promoter Disco Donnie sent to jail.

Album artwork for Eminem’s ‘The Eminem Show’

The end of Sasha and John Digweed’s iconic Twilio residency in 2001 had signalled a turning-point for fairweather trance and prog fans in the States, though the genre still reigned supreme in European clubs. Dutch DJ Tiësto took out the Top 100 DJs crown in 2002, 2003 and 2004, for example, before handing over the title to PvD and Armin van Buuren for the rest of the decade. Trance’s reverberations would begin to be felt once again in the States by 2007, as young Canadian producer Deadmau5 pioneered “nu-prog” with tracks like ‘Not Exactly’ and ‘Faxing Berlin’, best summarised as cleanly produced re-rubs of the progressive house sounds Sasha and John Digweed had been pushing several years earlier.

What’s really key is that despite dance music’s ups and downs during this time, the UK maintained an unflinching mainstream interest in dance music as a whole — something the States hadn’t managed to achieve since the fall of disco three decades earlier. Tracks like Eric Prydz’s big room, disco-sampling house pumper ‘Call On Me’ hit number one in Britain, while the same track skirted the U.S. countdown at a disappointing No.29 on Billboard’s Hot Dance chart. Several years earlier, Daft Punk’s ‘One More Time’ — a tune that would be repackaged as a classic of the EDM generation over a decade later — ranked at a poorly No.61 in America while hitting the No.2 spot in the UK. Big house tunes continued to rule the roost in Britain for much of the ’00s, with tracks like Mylo’s ‘Drop The Pressure’ or a raft of soulful Defected records hitting the commercial charts.

It’s fairly obvious, then, that when it came to dance music in the mid-noughties, the US and UK had very little in common. It was thanks to two disparate scenes on opposite sides of the globe that dance music would be able to break (once again) in America, and where EDM — as a genre, at least — would fully take hold.

Unlikely heroes of the forthcoming EDM movement, it was in fact French duo Justice that helped plant the seeds of EDM in American eardrums — much to their shared horror now, I’m sure. Their genre-defining LP ‘†’ proved ultra-successful Stateside, opening the door for similar-sounding producers like Fake Blood (‘Mars’), Boys Noize (‘& Down’), Bloody Beetroots (‘Warp’), Crookers (‘Limonare’) and early records from Steve Aoki and his Dim Mak gang. Justice’s ‘A Cross The Universe’ documentary (which followed them on their ’08 American tour) proved just how popular their metal-meets-dance-music formula had become, as the duo got into bloody fist-fights, body-surfed through mosh pits and had questionable interactions with young girls in green rooms (ew). Thrash electro and fidget sounds also resonated strongly with club kids in Australia and Justice’s homeland of France, as well as trickling into the UK alongside the booming dubstep and minimal scenes of the late ’00s. Dubstep (and later post-dubstep) would also prove hugely influential in the States, with young acts like Skrillex building on the template of UK producers like Skream, DJ Hatcha and Benga, before splintering into sub-genres like trap — something we don’t have time to go into now. The influence of David Guetta (the man who almost single handedly brought dance-music-infused pop music to the US charts) was equally pivotal in paving the way for EDM’s explosion — so much so that his story probably deserves a feature all of its own.

But why did Justice and co.’s sound have such a pick-up in the United States? The answer is simple: because this format — to American audiences at least — felt very, very familiar. It wasn’t dance music described as ‘rave’ (which conjured up scary images of ecstasy-dosed teens sucking on pacifiers in fluffy boots) but instead this was just a rock show with a few synths on the side. This new, non-threatening format was something that both hip-hop fans (Eminem) and frat boys (Nickelback) could get on board with — and this meant big, big bucks for anyone lucky enough to spot this trend first.

Over in Europe and running concurrently to the dance-rock and fidget scenes, another style of club music that would hugely influence EDM was reaching stratospheric popularity. Referred to as dirty Dutch, the scene was named after the label and radio show started by DJ/producer Chuckie, a man who had been attracting snapback-cap-wearing teenagers in their droves throughout much of the mid-2000s across the Netherlands. This big room sound with its enormous kicks and repetitive vox would go on to musically inspire much of the first wave of young EDM producers to really make it in America. Producers Nicky Romero and Hardwell had just hit the circuit when Chuckie’s ‘Let The Bass Kick’ landed in 2008 and would go on to form EDM’s first wave, followed by acts like Martin Garrix, Kygo, DVBBS and many more.

If fidget and electro-house had opened the door to EDM, then Swedish House Mafia were the first group to really grab it by the horns. They were the first real rockstars of the genre, complete with private jets, supermodel girlfriends and Beverly Hills mansions, commanding the kind of fervour (and fees) previously reserved for pop stars and the Hollywood A-list. Similar to fellow Swedish star Avicii, SHM weren’t just writing and producing club tracks — they were penning radio-viable records that also sounded great on a Funktion One. SHM failed to chart as successfully in the US as they did in Europe, but they once again represented the kind of non-threatening, formulaic and sing-along-style dance music that could delight both your festival buddies and your 12-year-old sister.

But it wasn’t just the music that was morphing format. Trance events like Sensation White had already made a name for themselves with big and expensive productions, but now DJs were commanding stadium-sized crowds who weren’t willing to pay £80 a ticket just to see a middle-aged man standing behind a set of CDJs. We needed pyrotechnics, we needed visuals, we needed stage managers running around in tiny headsets, and private jets, and Vegas residencies and ridiculous men with marshmallows on their heads because dance music had, suddenly, become a show.

Dance music’s new adopters in the States weren’t just presented with the records of artists like Martin Garrix et al — but with the big budget, high gloss musical experience that came along with it. Artists like Garrix, Avicii, Hardwell, even Steve Aoki’s cakes, represented not just a trendy music style, but a new opportunity of hedonistic escapism funded by corporations with endless cash. Rolling on Molly, talking about PLUR and making pilgrimages to Tomorrowland were all tropes of dance music’s new mega cult — and the industry was now worth more than anyone could have ever dared to imagine.

Electric Daisy Carnival in Las Vegas

The term EDM doesn’t represent just a style of music, a group of artists or a specific sound. It is, in fact, a way to describe the quick, lucrative and global commodification of dance music between 2010 and now. It’s a way to describe the conversion of DJs into brands — complete with complex social media strategies, image consultants and full-time security details — and festivals into retail marketplaces where people gather together to be sold things en masse. The shift from physical to digital formats in the last decade has diminished music sales as a revenue stream — instead, bolted-on ‘experiences’ that kids are willing to pay big bucks for are filling the void. Merchandise, tickets and VIP tables feed dance music’s all-powerful corporate juggernaut — no wonder Electric Daisy Carnival founder Pasquale Rotella wants to turn his festival into an “adult Disneyland”.

When I met Martin Garrix after his first Top 100 DJs poll win in 2016, he said something that crystalised why some EDM acts were more likely than others to remain successful post EDM’s bubble. “What I hate right now is that there is so much music out there that is just a copy of something else,” he told me. “I hate when everything sounds the same… I wanted to try something different. There’s so much music out there in this whole EDM thing that sounds so similar. I want to make my label more diverse.”

No matter what you think of the music of Martin Garrix (and other EDM producers of his ilk) it’s evident that the guy can pump out a well-produced, crowd-pleasing tune. More importantly, Garrix’s generation of producers are just as at home making millennial pop or mumble rap as they are making bangers for the Tomorrowland main stage, allowing them to shapeshift into new sounds far easier than the established house and techno elite.

What’s truly interesting about the DJs and producers who have successful surfed the EDM wave is how little loyalty they have to the sound itself. And why would they? It’s a medium based on instant gratification with a focus on huge drops and catchy chords, rather than the subtle peaks and troughs of more traditional dance music genres. Unlike underground purists, EDM artists haven’t spent years fetishising the origins or founders of their sound — because EDM as a genre simply didn’t exist before 2010 — making them freer to move onto something new.

Garrix has already stepped away from the ‘Animals’-esque chart-toppers that made him a star, preferring to pump out radio-friendly future bass cuts like ‘In The Name Of Love’ and ‘Scared To Be Lonely’ — a subtle but seemingly calculated shift as EDM’s popularity begins to wane. Armin, on the other hand, has continued to keep his toe in the trance pond with a smattering of vinyl-only sets and Tiësto recently released a deep house album, while Hardwell, Alesso and countless other EDM acts have begun dabbling in tech-house in an attempt to slowly transition into something deeper.

Ultimately, it’s the ability of these types of EDM artists to predict and follow trends that will make or break their careers in years to come — and why smart EDM producers are starting to actively build an audience outside the confines of the genre. Even DJ Mag’s (publicly voted for) Top 100 DJs poll experienced an influx in underground-leaning acts last year, showing it’s not just the artists that are slowly moving on — it’s the fans too. Maceo Plex, Black Coffee, Claptone and Solomun all entered the poll for the very first time in 2017, while Andy C, Paul Kalkbrenner, Disclosure and Richie Hawtin all re-entered after a few years left out in the cold.

Carl Cox & Friends stage at Ultra Music Festival 2016

What fans need to accept is that the term EDM does NOT mean d&b, techno, ambient, deep house or anything else for that matter, to anyone who’s been into dance music for longer than the last half a decade. It’s not an umbrella term, it is a way to describe the mutation of a music scene into a marketable product, symbolising a brief moment in time when the corporate world finally stepped on our turf. And just like pop punk, nu metal or any other mass-appropriated genre that’s come before it, EDM has already begun to exceed its expiry date. The EDM crash has well and truly begun, and as the last glowing embers of the genre gently fizzle into obscurity, it’s making way for an all-new and potentially even bigger trend.

After all, techno is the new EDM — don’t you know?

October 10th, 2018